Adieu, Bill Knott

Today is truly a sad day in literature. I am utterly shocked and regretful finding out that Bill Knott - one of my poetry idols, my model of a political poet, critic, contrarian, anti poet- is no longer living.

Published under the pseudonym Saint Geraud, a name he found in a French pornographic novel, Bill Knott’s first book contained some of his most powerful and most quoted work, including two poems that could do double duty as epitaphs.

Virtuosic with compact verse, Mr. Knott needed but three lines for his poem “Death”:

Going to sleep, I cross my hands on my chest.

They will place my hands like this.

It will look as though I am flying into myself.

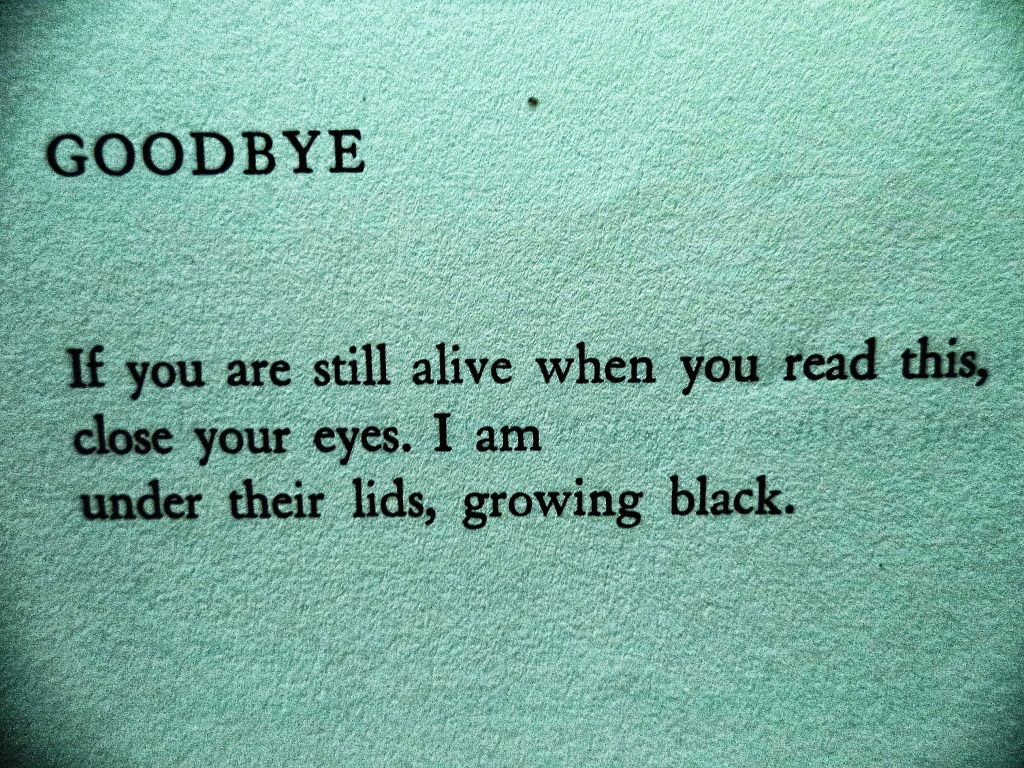

With eight fewer words, “Goodbye” is shorter still:

If you are still alive when you read this,

Close your eyes. I am

Under their lids, growing black.

Widely admired on the page and in the classroom, Mr. Knott taught at Emerson College for more than 25 years, published many books of poetry, self-published uncounted others, and was awarded the Iowa Poetry Prize.

Mr. Knott, who wrote his first book of poetry while working as a hospital orderly, died of complications from heart surgery yesterday, March 12 in a Bay City hospital, not far from his home. He was 74 and had moved a few years ago back to the state of his youth.

Although he told one interviewer he thought his work fell “within the minimalist or imagist tradition”, Mr. Knott ranged easily through poetry’s many forms, writing longer works in rhyming couplets, villanelles, sestinas, sonnets, haiku, and one-line bursts. Poets Mary Karr and Robert Pinsky, a former US poet laureate, each praised Mr. Knott in The Washington Post’s “Poet’s Corner” feature. In 2008, Karr noted how Mr. Knott exercised the power of brief verse after US bombs accidentally killed children during the Vietnam War:

The only response

to a child’s grave is

to lie down before it and play dead.

“Knott is not the type to win prizes, become the pet of academic critics, or cultivate acolytes”, Pinsky wrote in 2005. “But this thorny genius has added to the art of poetry”.

Knott’s voluble self-flagellation may have been some strange play for publicity, but the facts of his biography raise the uncomfortable possibility that at least some of his stunts — even, perhaps, his faked suicide — were expressions of unbearable inner turmoil. Like his alter ego, Saint Geraud, Knott was an orphan. His mother died when he was six, his father died when he was eleven, and he lived in an orphanage in central Illinois for eight years. He did a stint in a state mental hospital —“How I survived that hell I’ll never know”, he once said — which was followed by two miserable years on his uncle’s farm, and two more in the Army. In his later life, Knott faulted himself for not being able to turn these experiences into poetry. But, here, as in most things, he protested too much. One of his best poems, “The Closet”, takes us back, wrenchingly, to the aftermath of his mother’s death, when he was six years old:

Knott’s voluble self-flagellation may have been some strange play for publicity, but the facts of his biography raise the uncomfortable possibility that at least some of his stunts — even, perhaps, his faked suicide — were expressions of unbearable inner turmoil. Like his alter ego, Saint Geraud, Knott was an orphan. His mother died when he was six, his father died when he was eleven, and he lived in an orphanage in central Illinois for eight years. He did a stint in a state mental hospital —“How I survived that hell I’ll never know”, he once said — which was followed by two miserable years on his uncle’s farm, and two more in the Army. In his later life, Knott faulted himself for not being able to turn these experiences into poetry. But, here, as in most things, he protested too much. One of his best poems, “The Closet”, takes us back, wrenchingly, to the aftermath of his mother’s death, when he was six years old:

Here not long enough after the hospital happened

I find her closet lying empty and stop my play

And go in and crane up at three blackwire hangers

Which quiver, airy, released. They appear to enjoy

Their new distance, cognizance born of the absence

Of anything else.

Mr. Knott devoted one of his blog pages to collages he created from the many rejection slips he received. He also posted his art online, and illustrated with drawings some of small books he made by hand, creating beautiful keepsakes his friends and colleagues treasured. After publishing his collection “The Unsubscriber”, Mr. Knott largely used the Internet to distribute his work for free through his blogs, but he also sold his work via Amazon, where most of his self-published books are listed as out of print. On March 7, he published on his blog what it would have been his very last poem.

Living his life as performance art, as tragicomedy, he changed my ideas of what poetry is and can be.

It's late right now and I'm fading a little. Goodnight, Bill Knott, you one of a kind.

We brush the other, invisible moon

Its caves come out and carry us inside.

Comments

Post a Comment